Judeopolonia

Iwo Cyprian Pogonowski

Fragment książki "Jews in Poland" - New York 1998, str. 297.

Pro-German Zionists formed the Zionist Association for Germany in 1897 and elected as its president Max I. Bodenheimer (1865-1940), who served until 1910. In 1902 Bodenheimer wrote a memorandum to the German Foreign Ministry in which he claimed that Yiddish, spoken by millions of East European Jews, who lived in the provinces annexed from Poland by Russia and Austria, was "a popular German dialect," and that these Jews were well disposed to Germany by linguistic affinity. Bodenheimer stated that Zionism was currently controlled by pro-German leaders, and that Germany's support for Zionist goals would be a boon to German ambitions in the Near East and would earn the gratitude of the entire Jewish people. "The influence of Jewry in foreign lands would accrue to the benefit of Germany..."

On Aug. 11, 1914, Bodenheimer submitted another memorandum to the German Foreign Ministry on the "concurrence of German and Jewish interests in the World War." On Aug. 17, 1914, the German Committee for Freeing of Russian Jews was founded by German Zionists including Max Bodenheimer, Franz Oppenheimer (1864-1943), Adolf Friedmann (1871-1933) and Russian Zionist Leo Motzkin (1867-1933). The German Foreign Ministry supported the founding of the new committee.

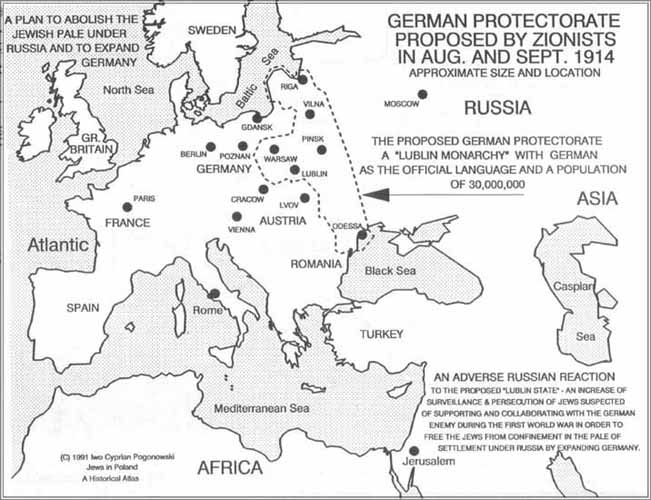

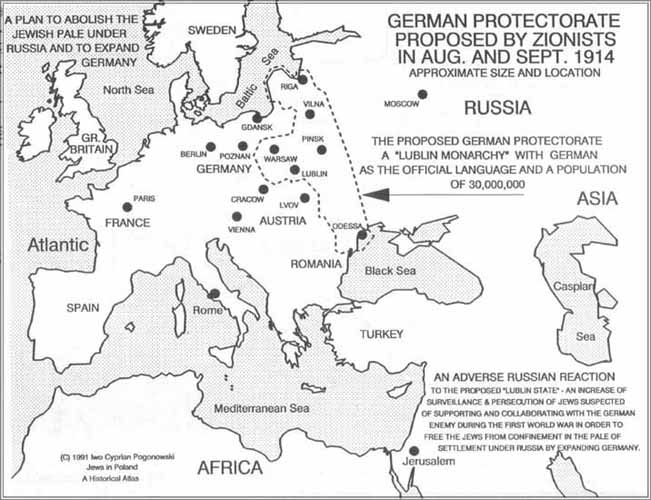

In Sept. 1914 the German Committee for Freeing of Russian Jews sent voluminous documentation about the Eastern Jews to the German Foreign Ministry and proposed establishment of a "buffer state" within the Jewish Pale of Settlement, composed of the former Polish provinces annexed by Russia. The new committee warned against the resurrection of a Polish national state and the danger of the Polish irredentist movement in the territories annexed from Poland by Germany and Austria. Thus, the Poles were the group to benefit the least from the establishment of the proposed new German protectorate.

The new buffer state was to have been dominated by some six million Jewish inhabitants, while other nationalities would counterbalance each other. The Jews would be most important because of their distribution, control of trade, and high literacy. Hatred of Russia and fear of other national groups in the buffer state would make them dependent on German protection and support. The new buffer state was to be a monarchy under a Hohenzollern prince from Berlin. Lublin was to be its capital because it was the seat of the autonomous Jewish national parliament, the Congressus Judaicus, before the partitions of Poland.

The population of some 30 million of the proposed buffer state or "Lublin Monarchy," was to be composed of autonomous groups of 6 million Jews, 8 million Poles, 11 million Ukrainians and Byelorussians, 31/2 million Lithuanians and Latvians, and under 1/2 million Baltic Germans. The official language, culture, and the officers' corps of the new monarchy was to be German.

Major Bogdan Hutten-Czapski, a "Polish-German" from Posen (Poznan) who was serving in the German General Staff, was assigned to evaluate the proposal for the new buffer state as a part of his task to encourage revolutionary and nationalist movements among the diverse ethnic groups which inhabited the former Polish provinces annexed by Russia in 1772-1795. On Hutten-Czapski's recommendation the proposal was rejected as utterly unrealistic. Eventually, the World Zionist Organization separated itself from the proposal. Jewish philosopher and defender of the Eastern Jews, Martin Buber (1878-1965), at first supported the proposal for the Lublin state. Later he withdrew his support from the idea of a "Jewish state with cannons, flags, and military decorations." One of Buber's associates, Julius Berger, wrote that the whole proposal of the Jewish buffer state verged on criminal irresponsibility and that it was the product of an irresponsible political dilettantism, which resulted in an increase of negative attitudes of Poles towards the Jews. Berger felt that antagonizing the Poles was dangerous in view of the fact that nobody could predict who would control the politics of Poland after the war.

Bodenheimer and Oppenheimer were given a promise from Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) and E.F.W. Ludendorf (1865-1937) that German Jews would be used as trustees of the German military and civilian authorities in the occupied territories populated by Eastern Jews. The name of the Committee for Freeing of Russian Jews was changed to the Committee for Eastern Affairs. Even in this new form, the committee did not succeed in representing all German and Austrian Jews. However, after 1916, the committee acted as an anti-Polish pressure group in Berlin and kept on stressing the common interests of Jews and Germans in Poland. Oppenheimer, embittered by disagreements with other Zionists, told his audience, "We are Germans to the last drop of blood."

Martin Buber wrote in Der Jude (a monthly magazine) in the fall of 1917 that the Germans were losing importance for the Eastern Jews and that many Poles, who might be left in control, saw Jews as "parasites and uninvited guests, who sooner or later must leave Poland."

The idea of a Jewish Lublin state was used in German propaganda in the most sinister way during World War II. For example, of the 70,000 Jews delivered by the Vichy French to the Germans, many bought first class railroad tickets to travel from France to the "Jewish Lublin State" for re-settlement there. All of these people were murdered in Treblinka and in the vicinity of Lublin, where the Germans organized an extermination camp in Majdanek; there alone, in 1941-1944, some 200,000 Jews and 160,000 other Europeans, mainly Poles, were murdered. Max Bodenheimer died in 1940 in Palestine, a refugee from Germany.

Przybliżony obszar państwa buforowego (Judeopolonia), które miało zostać utworzone pod protektoratem niemieckim. Z projektem tym wystąpił w 1914 roku Niemiecki Komitet Wyzwolenia Żydów Rosyjskich.